Embracing Illiquidity and Finding Your Investment Zen with Private Markets

Listed markets offer you money more or less when (you think) you need it, which might just be at the worst possible time - private markets can offer superior returns sans the drama.

One of the greatest dilemmas faced by any self directed investor is how to balance the liquidity profile of your portfolio. Many investors feel a sense of creeping unease at the prospect that their hard earned money may not be available when needed - in an emergency, for a better opportunity or even just to spend on something you want at a given point in time. The availability of liquidity, however, means that investors may also be prone to taking that liquidity out of the market at exactly the wrong time. Investing in less liquid private markets may help to take away this moral hazard, keeping investors on track for a longer term return target.

Just because it’s liquid doesn’t mean you should drink it

Trading software is generally designed to stimulate users into a state of arousal not dissimilar to what you might find in a casino. There are lots of flashing lights, prices flashing red and green, news feeds scrolling down the side of your screen with the latest market nights, little prompts with trading ideas etc - all designed so that you maximise time spent on the platform and move into a state of anticipation that increases the likelihood of generating a trade, and thus trading fees. Just like a casino, the more you play, the more your trading platform earns.

The problem with this of course is that one feels compelled to act when perhaps the best course of action is to do nothing.

Let me paint you a picture;

You have been doing some research and you come across XYZ Chips a brand new semiconductor company creating cutting edge chips which are going to undercut incumbents on price and capture market share. You decide to invest at $1.50 with a long term horizon. It’s got slightly high P/E ratio but that’s more than ok for a growth stock.

Imagine a few weeks later you log in to see XYZ in free-fall, your headline balance is flashing red with every passing moment - you wait a few minutes and you’ve lost yet more money. Signals are all in sell mode. The world is ending and if you don’t act now you’ll lose everything. Fearing the worst you generate your sell order. Forget limit orders, things are moving way too fast - you quickly submit your market order and it fills instantly, albeit even further down that the last time you looked - but at least you are out.

You get up and wash your face with some cold water contemplating what just happened. Once the dizzying nausea subsides you go for a walk and get some fresh air. A few days later you feel you can face your trading platform again, you get back to your computer and the storm has passed. XYZ is green. In fact, it’s a up a little from where you sold out. Never mind - it looked like it was going to zero. Over the next few days its climbs a little further, and in a few weeks its up well past your original entry point.

A month down the track some good news comes out and XYZ is on a tearaway - your original investment thesis has come to fruition and the market has realised what’s happening. It’s now up over 100% from your original entry point. Not wanting to be left behind you generate buy order. Because it’s moving so fast you don’t want to risk a limit order, so once again your order is executed straight away, a just a little higher than what you thought. Relived and grateful to be back in you sit back and relax. A few months later the stock has risen by as much as it dropped during your own ‘red wedding’ and you decide to exit. Your trading platform registered a nice little green profit, and you evened out your losses. Right?

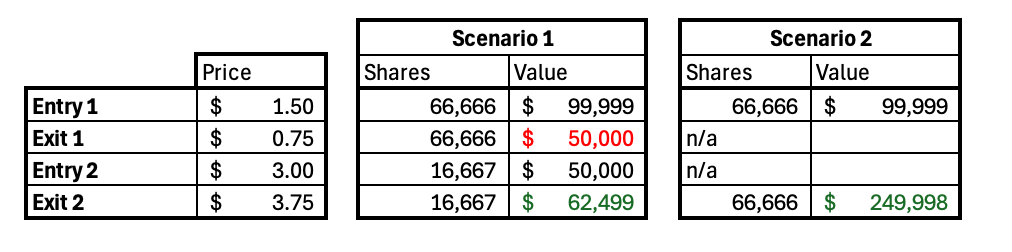

Err, no. In fact you have been whipsawed my friend, and you are well behind. Here’s quick spreadsheet to illustrate:

What I have described above represents Scenario 1. An approx. 50% loss on your original position. Re-entering the position after a 100% gain on the original entry price with the remaining capital, then allowing it to grow by $0.75 results in a modest gain, before selling. In total, this trading approach has resulted in a total -37.5% return. This is nothing to feel good about and you would have been much better off leaving your money in an at call cash account.

Imagine now Scenario 2, in a parallel universe. You enter at the same price as Scenario 1, at $1.50. Instead of panic selling you just held on. In fact, you had such strength of conviction in your position that you weren’t really watching the market at all. If you had, you’d realise the whole market was down, and you stock was just along for the ride - the price drop actually didn’t have anything to do with fundamentals at all. Long ago, shortly after executing your buy order you had set a sell limit order at $3.75. This executes while you are sitting in a work meeting (your Apple Watch buzzes with the confirmation). It’s a nice tidy profit of 250%.

Same stock, same initial entry price and same final exit price, with totally different outcomes. The kind of emotion led trading illustrated in Scenario 1 can happen in any investment product linked to a listed market, because liquidity provides a bias to act for those so inclined.

If XYZ Chips was a private company (lets say for arguments sake as a holding in a venture capital fund you have exposure to), then you would have had no opportunity trade it because there would have in all likelihood no mechanism to do so in the immediate term. Rather, you (or your VC fund manager) would wait for the optimal time to sell the asset in the future.

Information and liquidity

With the extraordinary proliferation of investment products in the listed market, individual investors can, today, build a fairly diversified portfolio using cash, listed shares and listed products that gain exposure across a range of asset classes - each with a different underlying liquidity profile.

The great challenge of anything listed, however, regardless of what the exposure represents, is that it is generally subject to the supply and demand of underlying investors - meaning price fluctuations and volatility. Prices can move around dramatically and may not necessarily (and in a lot of the time probably won’t) reflect the fair value of underlying assets at any given point in time. This can lead to emotional whipsawing where individual investors buy in the ecstatic frenzy of rising markets and sell in the despair of falling markets. It is this perception of liquidity that can facilitate emotionally led bad decisions, when investors might in fact be best placed to just ride out shorter term volatility.

There’s a range of academic views of how listed markets actually work, from the “Strong Form Efficient Market Hypothesis” which suggests all available information is automatically incorporated into prices and therefore all assets trade at fair value all the time. If you are a strong believer in passive investment vehicles then this is probably where you sit.

At the other end of the spectrum is “Inefficient Market Theory” which suggests that prices don’t reflect all available information perfectly and will fluctuate due to emotions, information asymmetry or other factors. This is where active investors philosophically align themselves.

Enter: private markets

Beyond listed markets, of course, there are private markets - where companies are not compelled to make information publicly available, there are limited disclosure requirements and investors are relatively free to act on asymmetric information. Private markets are, therefore, by virtue of their structure ‘inefficient’, and provide a significant opportunity for investors who know what they are doing.

The ‘trade off’ for private markets, however, is that they are illiquid - which means you need to commit to the investment for a period of time before liquidity is available, and in the case of funds, before distributions or withdrawals become available. For this reason private markets assets are typically expected to earn an ‘illiquidity premium’ - a premium above and beyond that of listed markets.

If you are investing in a fund, rather than an asset directly, then the fund should state the length of time they expect the investment to be illiquid for in the terms. For a private credit fund this might be as short as 1-2 years, and for a Venture Capital it might be 10+.

Matching liquidity with investment timeframes

Whether they realise it or not, not investors should already be both familiar and comfortable with the idea of illiquid investments. For example, many investors will be splitting their assets across real estate, retirement savings and another seperate investment portfolio.

Real estate is a classic illiquid investment in that its typically purchased (often as the family home) with a long term outlook and is not expect to be traded on a daily basis (and more than likely won’t be sold during a rough market unless absolutely necessary). Likewise, a retirement savings account is a very long term investment which most people won’t access until very late in their life.

In both these examples, we are talking about a very long term investment time frame. For a younger investor this might be as long as 20, 30 or even 40 years. In this context building a ‘middle ground’ into a portfolio for a 2-10 year liquidity outlook should be perfectly reasonable, and indeed prudent if it provides a differentiated source of return from listed markets.

Liquidity, Liquidity, what is it good for?

I’ve personally found that investing in private assets definitely takes a lot of the drama out of investing, because there’s limited opportunity to act during the investment term and I’m not under the constant daily bombardment concerning the minutiae of market movements concerning my investment.

When you are in the listed markets, watching your investments bounce around with the fear / greed cycles can age someone years if you haven’t trained yourself to tolerate these movements. Personally, it’s taken me some time to develop a ‘private markets mindset’ to investing in public markets.

What I mean by this is that when I invest in a company I do so with a medium to long term thesis in mind unless that thesis fundamentally breaks down I’m not going to sell until it hits my price target. Basically, I consider my public markets assets to be illiquid. I know why I have them, where I would be happy to sell and I don’t intent to sell them no matter how ‘Saving Private Ryan’ my position might look.

Lack of liquidity can be frustrating at times, but if you have done your due diligence and appointed a competent manager who communicates well, private assets can deliver above market returns for a part of your portfolio, and I’d suggest it does so in a much less stressful way than a public markets investment.

If you invest in technology (and I’m assuming you do if you are reading this), then Venture Capital, for example, can be a great way to get exposure to private markets and align with your investment approach.

If you want to find your investment Zen, private markets might just be worth a look.