Diversification Inverted with Venture Capital

While Venture Capital turns many of the rules of traditional portfolio theory on their head, there is method to the madness for managing risk and delivering portfolio returns

Venture Capital (VC) funds embrace an extreme form of diversification, based on the ‘Power Law’, which means they derive the majority of returns from a single, or small number of positions

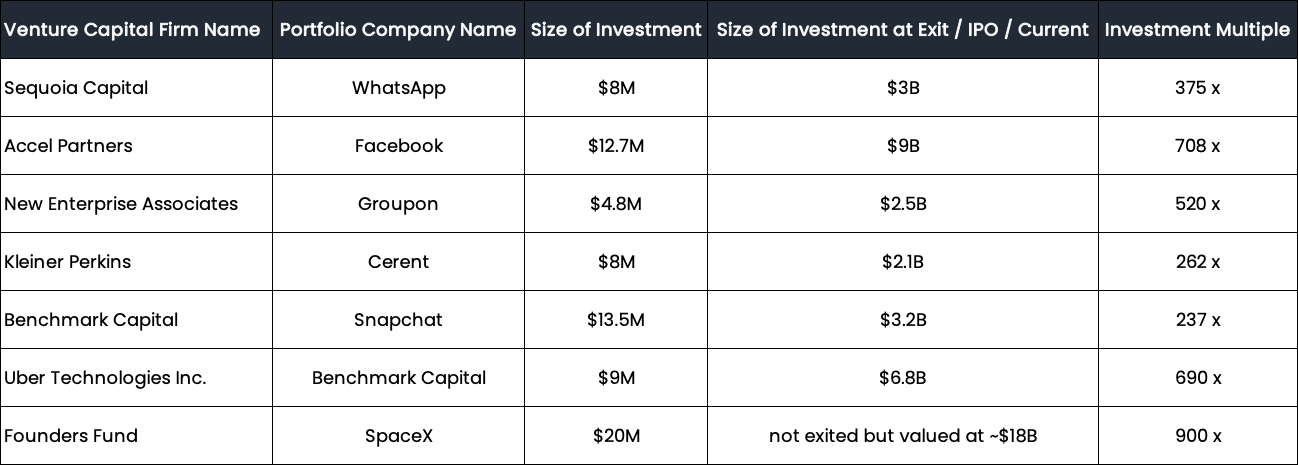

They are numerous examples of venture capital investments returning capital several hundred times over, more than offsetting the unsuccessful investments in a VC fund and delivering strong overall returns for investors

Picking a VC fund can be tricky, but investment team expertise, networks and experience are key for increasing the likelihood of an outstanding return.

As a keen young student of finance, I recall my eager anticipation of early lectures on Markowitz portfolio theory, believing I was being handed the keys to the future billions I was going to make. (Insert canned laughter). As the lectures ticked by, like everyone who studies it, I learnt that there is no ‘free lunch’ and that the closest we can hope for is the reduction of overall portfolio volatility through diversification across a large basket of securities, which creates a more reliable, albeit moderate rate of return. This is an interesting phenomenon and combined with the effects of compounding by reinvesting dividends, is a great way to build wealth slowly over time.

But really, I yearned for more excitement and through my career I continued to be drawn to the stories of entrepreneurs who had built extraordinarily successful businesses from scratch, creating extraordinary wealth for themselves, and for their investors, along the way.

The Venture Capital firms who fund these sorts of businesses at an early stage can have a bit of a mixed reputation. On the one hand they can been seen in an almost mystical light, divining the future through their deep technological expertise and strategic foresight. On the other, they can be depicted as greedy opportunists or even reckless cowboys, wrestling the dreams of wide-eyed founders to deliver a return at any cost.

Given I work in venture capital I’m inclined toward the former view, though the nature of each VC firm will vary greatly from one to the other. What is clear, however, is that most of the largest tech companies would not exist today if it wasn’t for venture capital, and indeed the very nature of the global technology industry, and perhaps technological progress itself, would be quite different without this funding mechanism.

I’ve met several people with an interest in start-ups who have started to invest in a very small number of early-stage businesses directly. If one of these businesses happens to be successful, this could prove to be very lucrative for them, or, more likely it’s a pathway to losses or capital locked up in perpetuity. For those wanting to invest in early-stage businesses, investing across a number of high-quality opportunities, rather than just a few, might provide a greater possibility of a pathway to success. This is where allocating to a venture capital fund might give you a greater opportunity for success in your investment journey.

VC Diversification and the Power Law

As anyone trained in finance knows, the traditional measure of risk in a portfolio is volatility (measured in the standard deviation of returns) and the traditional idea of diversification is to spread your portfolio holdings in such a way as to optimise the trade-off between risk and return so that you can maximise your return for the lowest possible level of ‘risk’, across what is referred to as the efficient frontier. This works well for transparent, liquid markets but less well once you start dealing with private assets that are valued less regularly.

Perhaps the key characteristic of VC vs other asset classes is the inversion of the diversification rule that governs the rest of the asset management world. Because VC’s expect such a huge asymmetric payoff on a very small number of companies, they are essentially accepting that a significant number of portfolio holdings aren’t going to generate a meaningful return, or may even be written off.

Of the holdings that are successful, the expectation is that they will be so successful, with such an outsized return, that one or two companies can generate all the returns in a portfolio. This phenomenon is known as the “Power Law”; the observation that a small number of investments in a venture capital portfolio generate the majority of returns, while the majority of investments either break even or fail to deliver significant returns – otherwise known as the "winner-takes-all" or "winner-takes-most" effect.

Some of the characteristics of the power law are;

Skewed Distribution of Returns: In traditional investment portfolios, returns often follow a bell-shaped normal distribution, where most investments cluster around the average return, and extreme outcomes are rare. However, in venture capital, returns tend to exhibit a highly skewed distribution, with a few outlier investments generating disproportionately large returns, while many others underperform or fail.

Highly Uncertain Outcomes: Venture capital investing is inherently risky, with a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the potential success or failure of individual investments. Many start-ups fail to achieve their objectives due to factors such as market dynamics, competitive pressures, execution challenges, or unforeseen obstacles.

Power Law Dynamics: Despite the high failure rate of individual investments, successful venture capital firms can generate attractive returns by investing in a portfolio of start-ups with the potential to become industry leaders or disruptors. The power law dynamics suggest that a small number of these investments will drive most the fund's overall returns, often by achieving significant growth, market dominance, or successful exits through acquisitions or IPOs.

Portfolio Construction: Recognising the power law dynamics, venture capital investors often adopt a concentrated investment approach, focusing their resources on a select few high-potential opportunities. By making larger investments in companies with the potential for outsized returns, venture capital firms aim to capture the significant value created by successful start-ups, even if many other investments fail to deliver comparable results.

Impact on Fund Performance: The power law has profound implications for the performance of venture capital funds. While a small number of successful investments can more than offset the losses from unsuccessful ones, this also means that the success of a venture capital fund is highly dependent on its ability to identify and invest in the right opportunities with the potential for significant growth and value creation.

So why a VC fund will need some diversification, over diversifying can be a risk to overall portfolio returns. This is because any one position might return the entire portfolio, and therefore every position must be sufficiently large enough to do so. Given the high risk of failure of the companies that a VC fund invests into, combined with the fact that technology companies are typically operating in a ‘winner takes all’ environment, it doesn’t logically follow that a VC fund should be over diversified.

The Power Law at play

To whet your appetite on exactly how this works, imagine a hypothetical VC fund of $100 million, which takes a $5 million position across 20 different companies, in each case taking a 20% stake in the business at that point in time with each company valued at $20 million.

Now imagine over the 10 year life of the fund that 19 of those portfolio companies failed and went to zero for one reason or another, however, one of them (lets call it “Winner Co”) found market traction and the company was able to exit at IPO at a valuation of $5 billion. This would mean the fund’s original $20 million stake in Winner Co is now a $1 billion return for the whole VC Fund, a factor of 10 times.

If you think these types of returns are fanciful, I’ve provided just several high-profile examples below to illustrate the fact that these types of outcomes can and do exist and are in fact what VC funds seek to uncover.

The point here is that while these types of returns most definitely aren’t a common occurrence, a venture capital fund only needs to find one of these investments per fund in order provide an exceptional outcome.

So that all sounds amazing, but what are the risks?

Venture capital is generally considered to be at the riskier end of the spectrum, though it is hard to measure. While there is plenty of performance data out there it’s subject to considerations like survivorship bias and selective self-reporting. Notwithstanding that, there are some ways to think about risk in venture capital.

Traditional portfolio risk is measured in terms of portfolio volatility, which makes absolutely no sense when looking at VC Funds. Because privately held, early-stage companies are valued only occasionally, it’s not really possible to measure VC risk as a function of company valuations (and hence rolling returns). If you were to do this, is the portfolio volatility would appear very low, however, which wouldn’t really reflect the risk you were taking.

Probably the biggest risk a VC fund faces is actually missing out on the opportunity to invest in the few companies that are going to generate the fund returns. For this reason, having conviction in the investment team’s ability to source, execute and manage deals is probably the key consideration from a risk perspective.

So rather than assessing VC funds in terms of their volatility profile, an investor might need to consider things like;

Technology Expertise: does the investment team have the suitable experience to identify new technologies and conduct product due diligence?

Investment team network: Does the investment team have a well professional network to source high quality deals?

Deal track record: does the investment team have a strong track record of executing deals, and what were the outcomes?

Business building track record: Does the investment team have a track record building early stage businesses?

Fund Record Analysis: has the fund been able to deliver returns to investors in previous funds?

Market and Macroeconomic Factors: Consideration of broader market and macroeconomic factors, such as industry trends, economic conditions, regulatory environment, and geopolitical risks.

Investing in VC Funds

As it currently stands there are around 9500 VC funds globally (and ~240 in Australia alone). They operate across different sectors, have different levels of experience and each have their own diversification profile in terms of sectors, investment stage, position sizing and geography.

With artificial intelligence now clearly emerged as the core technological platform of this next 20+ year innovation cycle, over the next few years there will be plenty of opportunity for these funds to invest in the next generation of leading technology businesses and generate returns for their investors - just in a very different way to a traditional diversified listed equity fund.